The 23 Best Movies I Watched for the First Time in 2023

Don DeLillo once wrote a short story about a sad, lonely man who spent all his days obsessively watching films, cataloguing the films he watched and then making notes on them, notes that only he ever read. Not sure why that’s on my mind… anyway, here are a list of 23 films I watched for the very first time in 2023.

23. The Lair of the White Worm (1988, directed by Ken Russell)

Sometimes a great movie is a great movie just because it’s so much fun. Russell mixes humour and horror better than any of his or our contemporaries, and he allots equal weight to a frank eroticism that would make most modern filmmakers clam up like preteens at their first school dance. If I was alive and in charge of giving out things like Oscars at the time, I would have awarded Amanda Donohoe for her untoppable performance as the seductive snake lady. Perhaps Donohoe didn’t convey the searing emotional pain of whichever actors won awards that year, but try asking them to do what she does in this movie. She’s ironic, intelligent, unnerving and scarily sexy all at once, and her acting is reason alone to see this, which also contains charming turns from Hugh Grant and Peter Capaldi.

22. Memories (1995, directed by Kôji Morimoto, Tensai Okamura and Katsuhiro Ôtomo)

Anime anthology with three films directed respectively by Kôji Morimoto, Tensai Okamura and Katsuhiro Ôtomo. All three are spectacular, but Ôtomo’s puts this in the category of essential viewing. His “Cannon Fodder” depicts the endless battles of a fictional 18th-century-ish European nation with its never-seen and possibly-non-existent enemies. The tale is an allegory for a fascism which uses war as a tool to foster obedience, and it’s effective enough in that vein, but what makes the piece incredible is the distinct texture of its animation and the illusion that the entire story is taking place in “one take,” a trick I’ve never seen applied to hand-drawn animation and which gives astonishing results. The other two films are exciting and atmospheric; Morimoto’s is a sci-fi mystery scripted by Satoshi Kon, and Okamura’s is a diverting apocalyptic comedy.

21. Carmen from Kawachi (1966, directed by Seijun Suzuki)

This year TIFF Lightbox held a Suzuki retrospective and I’ll be honest, I have trouble getting into the work of this filmmaker. I was able to appreciate this and the next film, however; I think I enjoy Suzuki best in his melodramatic mode. Carmen, not really an adaptation of the opera (though a fun rendition of Habanera is included) depicts the wanderings and vicissitudes of a young Japanese woman in a world of (what else) corrupt and exploitive men. Despite the premise, the gender politics are not simplistic, and Suzuki is continually successful in his satirical, melodramatic and photographic ambitions.

20. Love Letter (1959, directed by Seijun Suzuki)

More unabashed in its melodramatic tone than Carmen from Kawachi, this is the tale of a woman who leaves a good man in order to reunite with a lost lover who may or may not be dead. The journey takes her from urban haunts to a snowy, mountainous wilderness, and all of this is shot and blocked by Suzuki with a highly-precise emphasis on atmosphere, visual beauty and a tone so full of passion it edges toward ironic without ever crossing that line. Probably, the tonal consistency is supported by the film’s 40-minute running time. Despite the length, as the story ended I was very satisfied.

19. Our Sunhi (2013, directed by Sang-Soo Hong)

Very standard Hong story about a lovable woman (Yu-Mi Jung) and the possessive feelings she inspires in three self-centered men. Hong could be the most ascetic filmmaker in history, often it feels like he uses about six stock camera angles and he consistently recycles the same situations, themes and conflicts; and yet, each of his many films feels like a fully distinct piece, with its own particular interests and concerns. This film, I think, is a little more sympathetic to the men than some of Hong’s other work; they can’t help their neediness, and their petty ego trips are endearing to anyone who’s been there. The last scene is a poignantly simple comment on the void that women fill in men’s lives. Special mention for late actor Sun-Kyun Lee, whose recent passing was a shock; this is one of four films Lee made with Hong; Lee’s performance here is typically funny, precise and engaging.

18. Keane (2004, directed by Lodge Kerrigan)

Painfully lifelike movie about a schizophrenic man (Damian Lewis) searching New York for his lost daughter, the reality of whose existence is not always clear. The man develops a relationship with a real woman and her daughter (Amy Ryan and Abigail Breslin, both incredible), and how he handles this relationship generates suspense that’s almost unbearable, but narratively brilliant. Famously, this is a companion piece to and quasi-remake of Kerrigan’s Clean, Shaven; but this film wisely avoids that one’s attempt to package the story in a pulp/crime framework. Perfect execution on basically all levels. Also, I knew I’d been watching too many films when I instantly recognized Stephen McKinley Henderson as a mechanic who only appears very, very far in the background.

17. The Eagle Shooting Heroes (1993, directed by Jeffrey Lau)

I understand Kar-Wai Wong produced this martial arts comedy so that he could raise funds to resume shooting his art-action-epic Ashes of Time; what an irony that, decades later, WeirdGeometry.com would name Ashes the weaker film (I’m sure Wong will be stunned). Heroes has the tone, pace, insanity and carefully-written bits of a Marx Brothers movie, but instead of Groucho and Chico there’s Hong Kong superstars Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung, Leslie Cheung and more, and instead of occasionally breaking into song the heroes occasionally break into wild kung fu throw-downs. This parody of Chinese swordplay epics is very funny, and hands down the funniest performance is by Carina Lau in male drag as a warrior who’s unapologetically horny for every guy s/he comes across.

16. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, directed by Rouben Mamoulian)

Fredrich March’s initial transformation into Hyde actually frightened me, as much for the unsettling strain of March’s acting as for the shocking makeup effects. As a pre-code horror movie, Mamoulian’s film is wonderfully and disturbingly frank about sex and violence and the convergence of the two. March’s performance as Hyde is rawer than you expect from acting of this period, it’s an unnerving and indelible piece of work which gains impact from, but is not defined by, the spectacular makeup. Miriam Hopkins is exciting in a wholly different way as the hooker-with-a-heart-of, well, let’s say bronze.

15. Safety Last! (1923, directed by Fred C. Newmeyer and Sam Taylor)

The anti-Semitic and racist jokes are pretty hard to stomach, but at least they’re few and far between. I’d never seen a Lloyd film, and I found him surprisingly modern in his aspect and performance, and the set-up and execution of his gags unfold with a fluidity that outdoes some of Keaton’s best work. Having said that, I saw this early in the year, and what sticks in my brain more than the humour are the revolting racist caricatures; such is the unfortunate condition of the classic film lover, I guess.

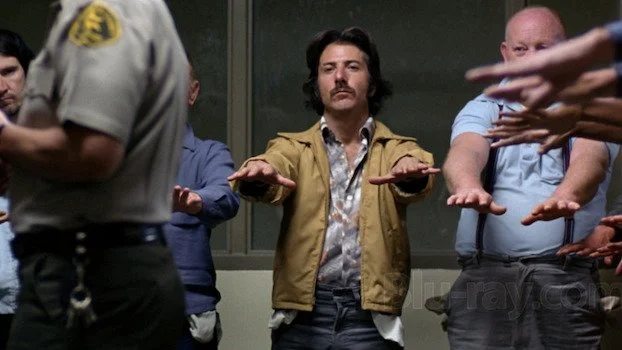

14. Straight Time (1978, directed by Ulu Grosbard and Dustin Hoffman)

Wonderful crime story. Ostensibly, this is a serious look at recidivism; in practice, the filmmakers get a lot more enamoured with Dustin Hoffman’s antihero once he gives up on the straight life and goes full criminal. Perhaps the film romanticizes this choice the way a real-life criminal would, and that’s the point, but I think it’s a lot easier to enjoy this as a fun Film Noir than a socially-engaged act of conscience. What’s especially lovely about this movie is the way it presents a juncture between the storytelling tropes of 1940s Film Noir and the idiosyncrasy of 1970s method acting, with the best qualities of both eras undiluted. Performances of rare delight by M. Emmet Walsh, Harry Dean Stanton, Gary Busey and, of course, Hoffman.

13. After Dark, My Sweet (1990, directed by James Foley)

I was tempted to call this a modern noir, but it’s over thirty years old, and it’s telling how Jim Thompson’s 1955 novel translates so naturally to the early 90s, whereas it would need a lot of revision to take place today. Anyway, a classic Thompson story about a drifter (Jason Patric) who gets involved in a kidnapping scheme hatched by a femme fatale (Rachel Ward) and a calculating ex-cop (Bruce Dern). Also typical of Thompson, each character is a lot more human than you – or they – expect. The actors are unforgettable. I’m inspired to look into what Patric movies I’ve missed; he and Ward create a believable romance equal parts toxic and affectionate. Dern is heroically sleazy. Also crucial is George Dickerson as a benevolent (?) doctor; Dickerson’s gaping smile masks unfathomable ambiguity.

12. Menace II Society (1993, directed by Albert Hughes and Allen Hughes)

A crime story that is genuinely socially engaged. Darker, less hopeful and more cinematically-assured than Boyz N the Hood. Boyz benefits from a cast full of superstars, but the comparative lack of star-power among the Menace cast perhaps lends greater impact to its horrified portrayal of juvenile crime in 90s LA. As in, there’s very little to idealize here. Hard to believe the Hughes Brothers were 20 when they directed this movie, nothing in the film indicates lack of professional or life experience on the part of the filmmakers. Among a lot of other fine qualities, I was impressed by the tightness and implacable logic of its crime narrative.

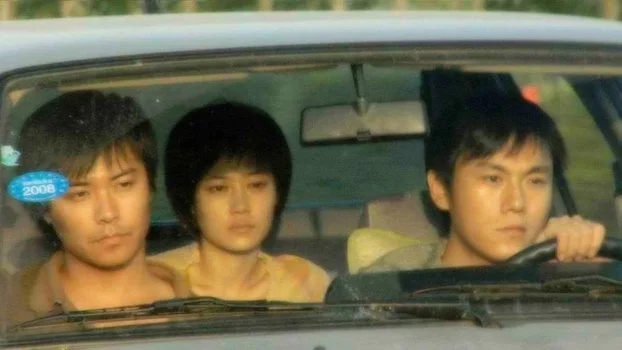

11. Better Luck Tomorrow (2002, directed by Justin Lin)

A crime story that is genuinely socially engaged, though the social message appears to be that Asian American characters can be just as venal, corrupt, dangerous and therefore human as anyone else, a message that feels just as rare today as it did twenty-one years ago. Follows a group of A+ Asian high school students who are just as proficient with crime as they are with grades. As a result of its ambitions, there’s a righteousness to the film’s amorality, which generates a fascinating, irresolvable ambivalence by the end. All actors are superlative, though lead Parry Shen probably lets his jaw hang open a little too often. Also, the existence of this film inspired one of the greatest Roger Ebert clips of all time.

10. Return of the Living Dead (1985, directed by Dan O’Bannon)

Once again, sometimes a great movie is a great movie just because it’s so much fun, and movies don’t get more fun than this. Alien screenwriter Dan O’Bannon directed this Night of the Living Dead [spin/knock]-off in which nothing can kill the zombies, not a bullet to the head, not decapitation, not even incineration. The undead in this case are unleashed on an assortment of 80s punks and their good-‘ol-boy elders, and watching both generations react to the carnage provides most of the fun. The stellar cast, astounding makeup effects and droll worldview set this apart from other horror comedies.

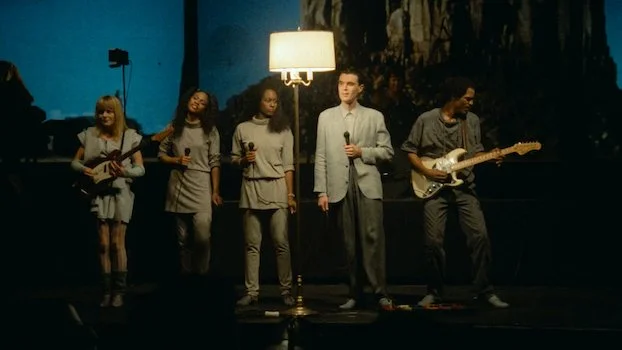

9. Stop Making Sense (1984, directed by Jonathan Demme)

Saw this at the IMAX re-release, and damn! Incredible music, inspiring execution, not a dull moment. You may fall in love with backup singer/dancer Lynn Mabry.

8. Seopyeonje (1993, directed by Kwon-Taek Im)

Definitely the saddest movie on this list, but the type of beautifully evocative sadness that leaves you more inspired than depressed. Tells the story of a contemporary Korean musician (Myung-Gon Kim) whose dedication to traditional Korean pansori music infects but nearly destroys his two sometimes-literally-tortured children. The dysfunctional family wanders Korea, trying and often failing to keep their beloved art form from becoming a casualty to modernity. This is not exactly a movie about the triumph of the human spirit, Kim’s father is genuinely abusive and some viewers may find it offensive just how willingly his daughter (Jung-Hae Oh) accepts the abuse; but the pain and the violence, the film argues, is the substance of life and, more importantly to this story, the substance of pansori. This is not a form of music I know or understand, but by the film’s final, breathtaking performance, I felt I glimpsed the history behind the music.

7. Eat Drink Man Woman (1994, directed by Ang Lee)

A family comedy that’s warm and comforting but not too sentimental. The story of an aging Taiwanese chef and his three beautiful daughters, Lee shoots the food as voluptuously as the women. I was lucky to see this on 35mm, and the richness of that medium combined with the sensuousness of Lee’s images and the natural feeling of the story amounted to a cinematic experience of great impact; by comparison, it’s disappointing that so many of today’s human stories are shot with the same meat-and-potatoes visual style. Oh, and I couldn’t discuss this film without celebrating Ming-Liang Tsai regular Kuei-Mei Yang, very funny here as the über-religious daughter.

6. City of Pirates (1983, directed by Raúl Ruiz)

This played at the TIFF Lightbox, and as I left the theater I heard more than a few of the usually-very-eclectic cineastes complain, one even described it as the worst film he’d ever seen. All of this to point out that I am even more patient and eclectic than your average art film buff, because I loved this admittedly inscrutable movie. But seriously, even I felt a bit restless in the first half of this occasionally cheap-looking nightmare about a woman’s interactions with ghosts and grotesques in an antiquated coastal city. Yet, as the film went on, I started picking up on the connections between some of its disparate ideas and characters, connections of a poetical nature, so that by the film’s climax each new image landed with mounting portentousness, and I found myself reflecting on ideas I’d never had before. In particular, the strange position of women who, by birthing men, are birthing untold murder and death on the world. Just as in his (deathless and superior) film Three Crowns of a Sailor, Ruiz imbues very simple effects with mystery and dread that’s hard to shake off.

5. The Music of Chance (1993, directed by Philip Haas)

Ironic allegory about two drifters who become indebted to a pair of ruthless millionaires and then must work it off by endlessly building a wall which serves no purpose other than to symbolize the debtors’ excessive wealth. The tale should be relatable to anyone who’s ever had to exchange time for money, and it’s the down-to-earth subject that keeps the allegory engaging. The drifters are played by Mandy Patinkin and James Spader, the millionaires by Charles Durning and Joel Grey; all four actors are spectacular, but Durning shines through as a one-of-a-kind performer whose boundless gravity is not diminished by his brilliant irony. The script was co-adapted by Paul Auster from his own novel; the film is probably an improvement of the book, because of the performances, and because Auster’s images gain a simple power when realized visually.

4. Spring Fever (2009, directed by Ye Lou)

Lou’s follow-up to Summer Palace and equally daring, about the gay underground of mainland China. The observations about shame and societal prejudice are moving, of course, but what makes this so involving is its liveliness. The performances have the spontaneity of real life; the story is full of surprises, but surprises motivated by character, so this never feels like melodrama.

3. Death Race 2000 (1975, directed by Paul Bartel)

Could be the closest thing there is to a live action Looney Toones movie. The respectable premise of this dystopian comedy is that America’s new favourite sport is a cross-country car race in which the competitors rack up points for every pedestrian they run over. The satirical points might be obvious but they’re delivered by all involved with such delirious commitment that they start to feel kind of profound, especially everything uttered by Don Steele as the deranged sportscaster/propagandist. The production and costume design, if it’s not exactly top shelf, has a creativity that’s exciting; the same can be said for the action. David Carradine is witty as the hero, Frankenstein, who will become President Frankenstein, and be addressed as “Mr. President Frankenstein” – this is objectively funny and you cannot deny it. Sylvester Stallone makes a pre-Rocky appearance and gives us a glimpse of what his career as a character actor might have looked like.

2. El (1953, directed by Luis Buñuel)

Shows you how much a movie can do at the same time. This plays like a parody of “kept women” Hollywood thrillers like Rebecca, Caught and Undercurrent, but somehow Buñuel’s humour never under-cuts the drama or tension of his story, so the audience can get caught up in the suspense and titter ironically at it simultaneously. The parallel tones seem easy because they play so naturally, but I’m hard-pressed to pick out any particular thing Buñuel does to make this work, and it’s something most directors screw up when they try. I guess it’s a particular alchemy in which only the greatest directors in history are initiated. You could say this is Buñuel’s Hitchcock movie – need I say more?

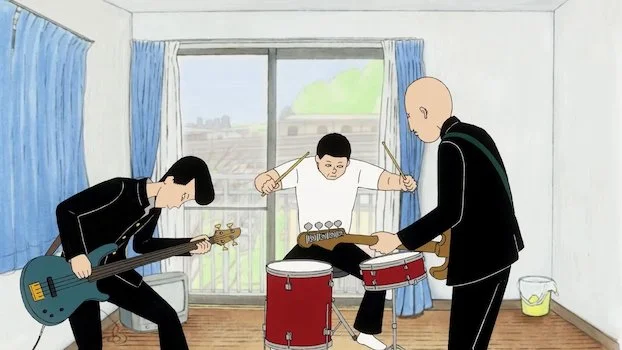

1. On-Gaku: Our Sound (2019, directed by Kenji Iwaisawa)

Very short, very dry, hysterical Japanese cartoon (not an anime) about a trio of tough high schoolers who decide on a whim to start a band. Though they can’t play their instruments, they manage to come up with a thirty-second riff that sounds pretty good, and before long they’re competing in a music festival with some equally quirky groups. The discovery that he’s capable of creating something beautiful discombobulates the lead tough guy in poignant and hilarious ways, leading to a climax of surprising tension and sublime humour. The film is an argument that artistic expression is crucial, even (and perhaps especially) for the least expressive people. It’s also just very funny, albeit in the driest, quietest register. A couple years ago my favourite discovery was Linda Linda Linda, another film about Japanese high schoolers starting a band… what is it about this topic that captures me? I think it’s the humour; I’ve seen a number of Japanese comedies in the last few years that have just the right balance of dry wit and sunny humanity, so they can be inspiring but never cheesy. I wonder if this is a popular genre in recent Japanese cinema; I’d like to learn more about it and I hope more films like these make it to this side of the globe.