Revised and Visualized: Joel Coen’s “Macbeth”

NOTE: This is the first of a planned series examining film adaptations of works of literature. If you enjoy my writing and would like to support me, please consider ordering a print of one of my photos from my online store.

Adapting Shakespeare presents a peculiar challenge to filmmakers. Not only is there the deathless question of how to shoot and block the action without the limitations of a stage, but the filmmaker must decide which perspective to bring to dense texts that are often loaded with ambiguities. The weakest Shakespeare adaptations are the ones that simply recite a play without interpreting it; there is so much ambiguity in Shakespeare – both intentional, and the ambiguity that results from our not being privy to Shakespeare’s own perspective – that to superficially read the dialogue does not begin to get at the dramatic tensions that exist, or can be added, between the lines. Adaptors must interpret Shakespeare, and yet, they can go too far, forcing in so much political allegory or modern psychology that the words lose all meaning. Adapting Shakespeare is a balancing act, and each adaptation provides a chance to examine a new context in which the Bard’s words can either grow in relevance or atrophy in misjudged representation.

Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is an impressive balancing act indeed: mostly faithful to the play’s dialogue, setting and structure and yet taking drastic liberties with key story points and characters. He doesn’t force the play into being about something it’s not, but he does focus narrowly on certain elements while disregarding others. His filmic style is pointedly theatrical, apparently in an effort to foreground Shakespeare’s words and characters without too much cinematic translation, which makes his major story departures all the more fascinating.

The castle’s flat, clean floor could be that of a stage

(By the way, I am not a Shakespeare scholar, so I cannot confidently give Coen credit for originating his changes; if readers are aware of earlier precedents for some of the revisions I’m about to discuss, please post them in the comments.)

Coen makes certain cuts and rearrangements in order to emphasize his take on the story. In the play, before Macbeth and Banquo come across the Witches, the First Witch describes a poor sailor whom she has supernaturally tortured in petty revenge against the sailor’s wife. This anecdote is entirely cut, although Coen retains a few lines that on the page refer to the sailor, and changes the order of the lines so they now refer to the Witches’ intentions toward Macbeth instead:

I’ll drain him dry as hay

Sleep shall never night nor day

Hang upon his penthouse lid

He shall live a man forbid[…]

This is a small change, and yet crucial for setting a particular tone. In the text, the Witches’ intentions are never stated explicitly and their precise disposition toward Macbeth is an ambiguity that could be handled a range of ways. The Witches could be adapted as impartial witnesses to Macbeth’s downfall or as the malevolent inciters of it. The former approach could allow Macbeth a greater degree of free will, while the latter makes Macbeth the unwitting target of a supernatural conspiracy. Coen’s decision to establish the Witches’ intentions as actively antagonistic toward Macbeth sets up the latter approach. In Coen’s version, Macbeth is a man who encounters evil Witches who draw him into a plot that will ultimately lead to his destruction. Since the audience knows the Witches’ intentions and Macbeth does not, his fate looms over everything, reframing his choices as the ineffectual efforts of a man to change an outcome he doesn’t realize has been set up in advance. The Witches are portrayed by Kathryn Hunter rather straightforwardly as embodiments of death itself – they’re costumed identically to Death in Bergman’s Seventh Seal, and take the form of crows – so it’s not a stretch to read Macbeth’s struggle against the inevitability of his demise as a dramatization of our own. Coen’s slight rearrangement of the Witches’ dialogue sets the stage for all of this – certainly another example of the director’s brilliant concision.

Right: Death, The Seventh Seal Left: The Witch, The Tragedy of Macbeth

Coen’s commitment to using Macbeth as a metaphor for the fatalism we all experience occasions the most striking reinterpretation of the play here: Denzel Washington’s characterization of Macbeth. The struggle of a man against the inevitability of his fate is certainly one element of the textual Macbeth, but it’s not the only element. Shakespeare was also concerned with contrasting definitions of manhood, valor and kingly authority, and examining the influence of women on power, all of which is more or less dropped in Coen’s version. Since these elements are woven inextricably throughout Macbeth’s dialogue, which Coen retains, their suppression amounts to some intriguing, counter-intuitive line readings by Washington in the climactic scenes. Washington’s Macbeth is a man on a journey toward acceptance of his own powerlessness and death; I don’t think “peace of mind” is a state often associated with Macbeth’s final scenes, yet Washington does project a kind of tranquility as he meets his end.

On the page, Macbeth starts out as the most heroic warrior in Scotland, and as he falls under the influence of the Witches and Lady Macbeth, he loses his moral standing, heroism, sanity, and valour – qualities that, to Shakespeare, befit both a good man and a righteous king (Macbeth’s degradation is driven home when Lady Macbeth chides him “Are you a man?”). The later scenes of the play find Macbeth descending into abject cowardliness. As Scotland breaks out in rebellion against his rule, Macbeth holes up in his castle, Dunsinane, relying wholly on the Witches’ prophecies – rather than his mettle in battle – to win the day. When Lady Macbeth commits suicide and the Witches’ prophecies are exposed as riddles that sowed his own destruction, Macbeth rebukes the Witches and joins the battle, come what may. Although he’s not exactly redeemed, he does reclaim some of the heroism that he lost when he submitted to Lady Macbeth and the Witches. Keep in mind Shakespeare wrote this play as a tribute to King James after the throne of England had passed to him from Queen Elizabeth, so the misogynistic subtext is not accidental.

“What makes a man?” Shakespeare asks, just like that classic Coen character Jeffrey (“Big”) Lebowski, and just like The Dude, Coen ignores the question. In Coen’s film, Macbeth’s arch begins to diverge from the text right after the first of the Witches’ prophecies comes true: when the trees of Birnam Wood appear to rise up and march on Macbeth’s castle. Here is Macbeth’s response in the text:

I pull in resolution, and begin

To doubt th’equivocation of the fiend

That lies like truth. ‘Fear not, till Birnam Wood

Do come to Dunsinane,’ and now a wood

Comes toward Dunsinane. –Arm, arm and out!

If this which he avouches does appear,

There is no flying hence nor tarrying here.–

I ‘gin to be aweary of the sun,

And wish th’estate o’th’world were now undone.–

Ring the alarum bell! Blow wind, come wrack,

At least we’ll die with harness on our back.

This is the point in the text when Macbeth begins to muster some of his old courage, and the next scene finds him on the battlefield. However, in Coen’s version, this speech is delivered with much sound and fury, but it signifies nothing: after shouting his lines, Washington slumps to a seat on his throne, already defeated, and the remainder of his scenes stay within the castle. His duels with Siward and Macduff are unchanged, but as his opponents have already penetrated Dunsinane, Macbeth’s loss is a foregone conclusion, and Washington’s performance and physicality throughout the fights projects his indifference toward the outcome.

In the film, the crucial turning point for Macbeth is not the above speech, but the one just before that, after Macbeth learns of Lady Macbeth’s death. It’s here that Macbeth delivers the famous “sound and fury” speech:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time:

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

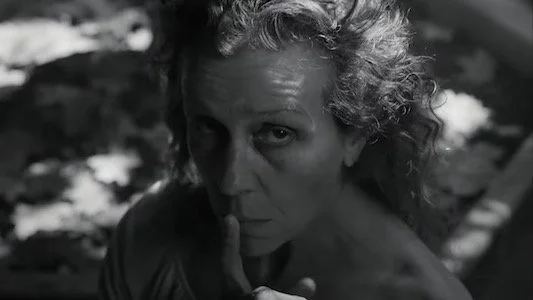

Whereas in the play this is a low point from which Macbeth ascends to reclaim some of his former glory, in the film this is more of a conclusive thematic statement, Macbeth’s articulation of the ultimate reality of life and death. Everything that comes after is truly just sound and fury, and Washington’s resigned performance portrays an awareness of what it all signifies. The shifted turning point gains much of its impact from the film’s sympathetic portrayal of Lady Macbeth; rather than the figure of pure malevolence that we often see, Frances McDormand plays her as a pragmatic woman acting out of genuine love for her husband. A less misogynistic depiction of Lady Macbeth certainly precedes this adaptation, but here it’s crucial in redirecting the emphasis of the story: for this Macbeth, the loss of his love is the critical moment, and decidedly not because it frees him up to regain his manhood.

On my first viewing of The Tragedy of Macbeth, I was most surprised by Washington’s soft read of his final lines, as he duels Macduff. In the text, this is the most conclusive moment. Macbeth has still been holding on to the Witches’ prophecy that he will not be harmed by any man “of woman born,” setting up the greatest plot twist of all time:

MACBETH Let fall thy blade on vulnerable crests:

I bear a charmèd life, which must not yield

To one of woman born.

MACDUFF Despair thy charm,

And let the angel which thou still hast served

Tell thee: Macduff was from his mother’s womb

Untimely ripped.

Macbeth’s response ties up his own arch and the play’s themes:

MACBETH Accursèd be that tongue that tells me so,

For it hath cowed my better part of man.

And be these juggling fiends no more believed

That palter with us in a double sense,

That keep the word of promise to our ear

And break it to our hope. I’ll not fight with thee.

MACDUFF Then yield thee, coward[…]

MACBETH I will not yield[…]

Though Birnam Wood be come to Dunsinane,

And thou opposed, being of no woman born,

Yet I will try the last. Before my body

I throw my warlike shield. Lay on, Macduff,

And damned be him that first cries, ‘Hold, enough!’

This is Macbeth’s final rebuke of the Witches, and the moment when he trusts his fate wholly to his own courage, becoming a little of the hero he was at the outset. But in the film, the italicized dialogue above is cut, perhaps because in Coen’s universe, the “juggling fiends” cannot be admonished, since they represent death itself. Washington plays Macbeth’s realization (“Accursèd be that tongue…”) and resolution (“Lay on, Macduff…”) with a hollow whisper, filled with resignation. It’s a performance seemingly at odds with the words, yet consistent with this version of Macbeth. The exchange is filmed in shot/reverse-shot close ups, and the casting of Corey Hawkins as Macduff adds an extra dimension. Hawkins is 33, the only other black actor with a prominent role in the film, and plays a type that reminds us of a young Washington: powerful, heroic, full of charisma and rousing speeches. At this stage, Macduff and Macbeth have each lost a wife, and as the camera cuts between their faces, we compare the stages of life: the young man, unable to conceal his grief and righteous anger, and the old man, worn down by life, staring death in the face with acceptance. It’s a unique angle on the scene, and aided subtly, but with brilliant economy, by simple film editing. Where another adaptation might switch into autopilot, here this scene, performed untold thousands of times for hundreds of years, is made fresh.

Right: Denzel Washington as Macbeth Left: Corey Hawkins as Macduff

After the film’s take on Macbeth himself, the largest changes involve Lady Macbeth and Ross, characters whose paths cross in this version in a startling scene that drastically revises one of the play’s most important moments.

Lady Macbeth’s character has been examined, revised and debated for hundreds of years and she will certainly not be summed up here, but suffice it to say, she’s often depicted as a villain who is undone by her own humanity. She goads Macbeth into killing King Duncan, but admits “Had he not resembled My father as he slept, I had done’t.” It’s hard to forget this line in the sleepwalking scene, when after her sins have driven her mad, she wails, “Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?” That is, when reading the play it’s hard to forget – in the film, the “My father” line is cut. Perhaps that is because, in this version, it’s not entirely clear that Lady Macbeth ever loses her mind, or suffers much guilt at all. McDormand’s Lady Macbeth is a cunning pragmatist who doesn’t look back once she decides on her plan; for her, all of the conflict stems from Macbeth’s inability to shake off his own guilt once he’s achieved the throne. When she admonishes Macbeth for not forgetting the past and enjoying his power, her dialogue can be taken as a statement of principles:

[…]Why do you keep alone,

Of sorriest fancies your companions making,

Using those thoughts which should indeed have died

With them they think on? Things without all remedy

Should be without regard: what’s done is done.

On the page, Lady Macbeth can’t follow her own advice and loses her mind with guilt; in the film, that’s not necessarily so. The sleepwalking scene is rendered excellently in Coen’s version; Jefferson Mays and Nancy Daly are compelling as the servants witnessing Lady Macbeth’s unconscious monologue, and McDormand brilliantly sells her insanity. But the scene ends with a twist: as Lady Macbeth exits, delivering her final lines “To bed, to bed…”, she turns to the servants, her expression suddenly lucid, and bellows her last “To bed” at them, both as an order and to indicate that she knows they’ve been watching all along. Her lucidity would imply that she is not sleepwalking after all, which begs the question of whether she is in fact losing her mind or only pretending to be. Indeed, this Lady Macbeth seems a little too sharp to go mad so abruptly; perhaps she has predicted Macbeth’s downfall and decided her best strategy to avoid retribution is to fake insanity. It’s ambiguous, but an ambiguity the film facilitates purposefully.

Of course, if Lady Macbeth were only faking insanity as a tactic of self-preservation, then she wouldn’t actually kill herself… and here enters Ross. This is the character who has undergone the greatest transformation from what he is in the text. In the play, Ross is almost indistinguishable from the other Scots who serve Macbeth for a while, catch on to his guilt, and join the uprising against him. In Roman Polanski’s 1971 film version (and perhaps in earlier stagings), Ross’ character is altered such that, unlike the other Scots, Ross is complicit with Macbeth’s crimes until it serves him not to be, at which point he switches allegiance to the rebels. This was achieved with only slight adjustments to the story: Ross replaces the textual Third Murderer who kills Banquo, and when he speaks to Lady Macduff before she’s murdered by Macbeth’s soldiers, the scene is embellished to have Ross in on the killing. The corruption of Ross was a pretty clever revision to show how tyrants couldn’t be tyrants without amoral opportunists, and to have some of the spirit of Macbeth live on after his death.

Coen builds on the revisions of the 1971 version and turns Ross into a fully realized character who’s essential to the plot and themes of the film. The changes set in place by Polanski’s version are retained and enlarged upon. Ross is costumed differently than the other Scots, in monkish robes that establish him as the religious arm of the throne (infer what you will about the relationship between religion and power). Ross is always placed just at the edge of the frame, listening, and Alex Hassell’s outwardly obsequious performance exudes an undertone of menace. Act 2 Scene 4, which in the text serves only as exposition, is rejiggered to imply a connection between Ross and the Witches. In it, after Duncan is killed and Macbeth throned, Ross and an Old Man share stories of nightmarish events in Scotland now that nature has been thrown out of balance by the murder of a king. Their speeches were written only to provide a sense of the state of Scotland under Macbeth, but Coen has Kathryn Hunter play the Old Man as another manifestation of the Witches, and her and Hassell’s line readings convey a sick pleasure in the evils they describe.

The collapsed shack at a crossroads where this scene is set appears again, when Banquo is murdered and Ross makes his first of two major interventions in the story. In the play, Banquo is murdered but his son Fléance manages to flee; he doesn’t appear again, but we infer that he lives on to fulfill the Witches’ prophecy and beget a line of kings (King James was thought to be a descendent of the historical Banquo). Coen extends the scene of Banquo’s murder to have Ross find Fléance hiding, and then cuts away, generating suspense as to whether Ross carried out Macbeth’s orders and killed the boy. The suspense is preserved later on: when Macbeth has his second encounter with the Witches, Coen cuts their prophecy that Banquo’s royal line will survive. This is all to set up the film’s final scene, which doesn’t appear in the play at all: it’s revealed the Old Man/Witch has been hiding Fléance for Ross. Ross’ motivations are open-ended, but we can guess he’s in the know about Fléance’s royal future, and has rescued him to align himself with forthcoming power. Since Ross appears to be allied with the Witches as well, we are not left with a rosy feeling about the future of Scotland. The final scene of the play is a lot more positive: King Duncan’s son delivers a speech about how things will be better now that Macbeth is dead and Scotland will be Anglicized (King James was king of both Scotland and England). The original ending means a lot less now that James has been dead for almost 400 years, so it’s no wonder Coen chose a denouement more fitting to his darker vision of the story.

Whereas in the 1971 version Ross is an opportunist who manages to evade retribution for his crimes, in Coen’s film he is a Cheney-like figure who controls events when no one is looking. There’s no better example than the “suicide” of Lady Macbeth. In the play, this occurs offstage, and when it’s reported to Macbeth the audience is given no reason to doubt that Lady Macbeth took her own life. In Coen’s film, we see Lady Macbeth wandering Dunsinane, either in a mad stupor or pretending to be. It’s a moment of chaos, the castle’s inhabitants flee in a panic as the rebellion approaches, and in the midst of it all, Ross spots Lady Macbeth atop a high staircase and his eyes light with inspiration. The camera cuts, and the next time we see the villainess she’s dead from a tumble down the stairs. I suppose you could call this ‘ambiguous,’ but the suggestion that Ross did her in is so strong it’s hard to doubt it. This simple change says a lot about both characters in this version. McDormand’s Lady Macbeth remains her calculating self, never going mad but only falling victim to an even more cunning schemer. Ross’ motivations are intriguing: he might have killed her to hasten the transfer of power he saw coming, but it was also an unnecessary risk. It’s possible, then, that Ross committed this murder strictly for pleasure.

As the most successful and least conflicted murderer in the film, it’s Ross who best embodies the spirit of this Macbeth. We are reminded of Lady Macduff’s words right before she is murdered (expertly delivered in this version by Moses Ingram):

Whither should I fly?

I have done no harm. But I remember now

I am in this earthly world, where to do harm

Is often laudable, to do good sometime

Accounted dangerous folly. Why then, alas,

Do I put up that womanly defence

To say I have done no harm?

In the earthly world she describes, where fair is foul and foul is fair, it’s a man like Ross who most belongs. In Coen’s Macbeth, unlike Shakespeare’s, the best we can do is accept that, not change it.

Alex Hassell as Ross