Revised and Visualized: Nolan’s “Oppenheimer”

American Prometheus, the non-fiction source material for Christopher Nolan’s blockbusting biopic Oppenheimer, tells the story of the Father of the Atomic Bomb with more facts-per-page than an average textbook. Since I read Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, I’ve been curious to see how Nolan would adapt such a complex historical narrative into a film designed to hold the attention of mass audiences. I had every expectation that Nolan would drastically condense information and pump up the action, that he would consolidate characters and introduce fictional devices to add drama; in other words, that he would resort to the usual strategies Hollywood filmmakers use when adapting messy real-life stories. The most astonishing thing about Oppenheimer, however, is how thoroughly Nolan was able to avoid fabrication or simplification, while shaping complex history into an exciting epic that could break box office records.

As a filmmaker, Christopher Nolan has many signatures, but he’s perhaps best known for his labyrinthine, non-linear narrative structures. Since entering the mainstream with his Batman films, Nolan continually tests how complex he can make his plots without straying too far afield from popular taste. With hit films like The Prestige, Inception, Interstellar and Dunkirk, Nolan took non-linear narrative devices that had previously been exclusive to niche literature or cult films and, with a Spielbergian combination of spectacle and emotional appeal, made these palatable to popular audiences. This is one of many ways in which Nolan is an innovator: he continually expands the definition of mainstream entertainment. Given this very unique CV, Nolan was probably the only filmmaker who could solve the puzzle: how to turn the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer into a blockbuster without dumbing it down for mass audiences? A puzzle perhaps only Nolan himself would conceive.

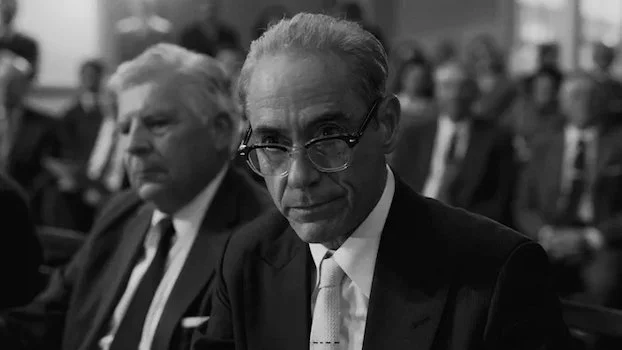

Unsurprisingly, Nolan’s solution involves narrative structure, and manipulating it in such a way that generates suspense even when audiences are well aware of the story’s outcome. Whereas American Prometheus narrates from the fully informed, historical perspective of its biographers, Oppenheimer is split into dual narratives, one from the point of view of Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the other from that of his antagonist, Washington power broker Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.). Each thread functions as a cinematic first-person narrative: the central character is in every scene, and the action is limited to what he knows or sees. By limiting the narrative exposition in this way, Nolan is able to set up mysteries and cliffhangers for Oppenheimer and Strauss, and pay these off with maximal dramatic effect.

Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) and Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.)

To complicate this approach, both threads are chronologically non-linear, and in subtly different ways. Oppenheimer’s story uses a traditional framing device: his early life and tenure at the Manhattan Project are flashed-back-to as these are investigated during the 1954 government hearing that destroyed the scientist’s reputation and career. In parallel, Strauss faces similar scrutiny during a series of 1959 senate hearings questioning his eligibility for Secretary of Commerce. The action during Strauss’ scenes mostly stays in 1959, with occasional flashbacks to moments when Strauss clashed with Oppenheimer. Although much of the film takes place in retrospect, Nolan sustains suspense by choosing when and how to reveal certain information to his audience and characters. With pointed irony, questions which are raised in one storyline are answered in the other. The impetus of Oppenheimer’s 1954 hearing is kept mysterious until late in the 1959 storyline, when Strauss reveals he personally manufactured the government’s persecution of Oppenheimer to satisfy a personal vendetta. Because of how Nolan has restricted information, this revelation unfolds as a plot twist, and the somewhat mundane reality of a government hearing takes on the stakes of a Shakespearean tragedy. It’s choices like these that keep the historical narrative exciting.

Using these complex formal devices, Nolan keeps his narrative on track while exercising much creative license with his various timelines. Dramatically, the film is roughly separated into about five movements, presented in chronological order: Oppenheimer’s introduction at Oxford to quantum physics, his coming into his own as a professor at Berkeley, his recruitment into the Manhattan Project and the scrutiny of his private life that this attracts, the creation of the atomic bomb and then finally the hearing that destroyed his career. During each movement, Nolan freely and frequently cuts away to the 1954, 1959 timelines and Strauss’ memories as each of these pertain to the present subject. While there are sometimes as many as four timelines at play, by always keeping the storyline focused on a specific period of Oppenheimer’s life, the effect is ironically linear. Nolan, as he often does, manages to implement highly complex – some would say convoluted – storytelling devices in order to achieve something your average audience member could understand.

It isn’t the non-linear storytelling alone that makes Oppenheimer exciting, but using this approach, Nolan implements a relentless editing style in which, like in another recent, unexpected hit, everything happens all at once. This is not a film comprised of deliberate scenes with a gradual accumulation of detail, it is a film in which the next scene has begun before current one has ended. Given the pace, and the ever-present Ludwig Göransson* score that drives the film, Nolan’s style has been compared to that of a movie trailer. Typically, this is not meant as a compliment, the implication being the style is geared for impatient audiences averse to being engrossed by a classical narrative. The comparison is not inapt but, in my view, it doesn’t carry the insult that’s intended. If non-linear cross-cutting and wall-to-wall music are hallmarks of trailers, it doesn’t follow that these are not valid storytelling tools if a filmmaker should decide to use them. Besides, in a way, modern trailers are each like miniature experimental films, constructing narrative coherence out of fleeting, disparate moments; if trailers have trained audiences to accept – or laude – a feature film that’s constructed this way, I take it as a sign that mainstream cinema could be moving in an interesting direction.

That said, Nolan’s pacing does require one to adapt to certain storytelling choices that are not often found in serious, historical films; for instance, his approach to character development. Take Oppenheimer’s early, doomed romance with troubled communist Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). It’s a crucial part of the story, as the affair draws suspicion on Oppenheimer during the 1954 hearing. The romance is also important thematically: Oppenheimer’s inner struggle between left wing radicalism and the priorities of the U.S. government finds dramatic expression in his tumultuous relationship with Tatlock, whom he eventually rejects to protect his position in the Manhattan Project. In a traditional biopic, you’d expect there to be a lot of Jean Tatlock, with detailed scenes that chart the rise and fall of her relationship with Oppenheimer. Instead, Nolan opts for shorthand, sketching the romance across three or four brief scenes, using a bouquet of flowers as a visual motif. At the beginning: Oppenheimer buys Tatlock flowers and she mocks his sincerity; in the middle: he buys her flowers again and she angrily chastises him for the conventional gesture; at the end: he buys her flowers, this time as an inside joke, and she throws them in the trash with a certain amount of affection, knowing this is what he expected. Rather than a lot of complex dialogue, we have a visual device that quickly depicts a relationship which is not perfect but ends at a place of mutual respect and understanding. This type of shorthand is commonly used to quickly sketch supporting characters in the kind of big budget action films Nolan usually makes; it’s less common in heady historical dramas. For viewers used to patient dramas in the mold of Spotlight, there may be an impulse to dismiss Nolan’s approach here as simplistic or lazy; my opinion is that there are very few subjects that demand a narrow set of stylistic approaches, this subject is not one of them, and given the kind of movie Nolan is making, his shorthand is effective and makes sense.

Oppenheimer with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh)

While Nolan takes wild stylistic liberties with the source material, he mostly proves unwilling to knowingly change facts, even when these facts conflict with one of the most popular legends surrounding the enigmatic scientist. Probably the second thing most people know about Oppenheimer, after his management of the Manhattan Project, is that when the first atomic bomb was detonated the man supposedly uttered this quote from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I have become death, destroyer of worlds.” In reality, Oppenheimer probably didn’t actually say those words at that time; he only said, years later, that the explosion reminded him of the quote. Regardless, most wouldn’t be bothered if Nolan “printed the legend” and gave the popular version of the story. The way Nolan handles the quote, however, fascinatingly reveals how he does and does not permit himself creative license with this story.

Nolan introduces the Gita quote early on, as verbal foreplay during a sex scene between Oppenheimer and Tatlock. In Oppenheimer’s Berkeley bedroom, Tatlock finds a Sanskrit copy of the Gita, which Oppenheimer reveals he’s taught himself to read. Tatlock points to a random page and teasingly asks him to recite; of course, it so happens she’s pointed to the infamous quote. While this scene is fictional, it has a generalized accuracy: Oppenheimer really did teach himself Sanskrit, really was taken with Hinduism, and surely intellectual quirks like these made him irresistible to the women in his life. Later, when the first atom bomb is detonated, Nolan has Oppenheimer repeat the quote – but only in voice-over, portraying his thoughts. By depicting the famous quote in this way, Nolan manages to honour the facts as well as popular expectations, while also applying his own layers of subjective interpretation onto the story. The film suggests Oppenheimer’s rejection of Tatlock partly motivated her eventual suicide; having the Gita quote associated with Tatlock prompts audiences, when the quote is repeated, to consider the “worlds” Oppenheimer has destroyed by his total dedication to the Manhattan Project: for example, the possible world in which Oppenheimer remained true to Tatlock and the left-wing causes that she represented. Nolan gives the famous story of the Gita quote new, personal implications for Oppenheimer, without deviating from the known historical narrative. This balance is definitive of Nolan’s approach to this material: he’s dedicated to historical accuracy, but not at all unwilling to add his own perspective to the story.

In one very important way, Nolan’s perspective even reaches beyond the contents of the book he’s adapting. American Prometheus mentions that in 1959 Strauss failed to be confirmed as Secretary of Commerce, but the book does not cover this period with much detail. In the film, the 1959 storyline reaches its climax when scientist David Hill (Rami Malek) gives devastating testimony against Strauss, exposing the unethical actions Strauss took to ruin Oppenheimer’s career. This event, while historical, is not even mentioned in American Prometheus, but its inclusion follows naturally from Nolan’s choice to make Strauss such a major character in the film. This was probably the largest change Nolan made to the source material; while Strauss’ actions are just as consequential in the biography, the book is not in any way structured around Strauss’ point of view. It’s clear that with Strauss, Nolan decided he had something of great storytelling value: a villain.

Nolan’s use of a villain demonstrates his characteristic strategy of keeping audiences engaged with the conventions of traditional storytelling so that they accept a higher level of complexity than they might if those conventions weren’t at play. In this case, moral complexity. Ultimately, Nolan isn’t interested in pushing audiences to arrive at a “correct” moral position on Oppenheimer, the atom bomb or Hiroshima, his goal is instead to leave audiences with a sense of the colossal importance of the subject matter. That could have been a little too heady for mass audiences, without the more immediate reward of witnessing a villain like Strauss get his comeuppance. My hunch is that if the film were much the same but with less of Strauss it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. To that end, one cannot underestimate the multifaceted brilliance of casting Downey Jr. in the role: not only does he give one of his all-time best performances, but surely many younger viewers were intrigued to see Iron Man play a bad guy.

What’s pretty incredible, also, is that the conventional entertainment value of the Strauss storyline deepens rather than cheapens the overall purpose of the film. In Nolan’s telling, Strauss’ villainy is motivated by his pettiness: after Oppenheimer deals Strauss a few careless slights, Strauss develops a grudge that drives him to destroy Oppenheimer. While American Prometheus offers some basis for this characterization, it’s probably true that Strauss’ ruthlessness was at least equally motivated by impersonal, political goals. Nolan chooses to emphasize Strauss’ egotistical pettiness to make a larger comparison between men like Oppenheimer, who endlessly consider the impact of their choices on the world, and men like Strauss, who only consider themselves. One of Nolan’s more ominous suggestions is that the U.S. has had a lot more Strausses than Oppenheimers in charge of nuclear weapons: from the Secretary of War (James Remar) who spares Kyoto from the atomic bomb because that’s where he took his honeymoon, all the way up the chain to President Truman (Gary Oldman), who (in Nolan’s version) seems to think of Hiroshima and Nagasaki only in terms of his personal legacy. If portraying Strauss as such a clear villain may have simplified the narrative for some audiences, doing so also allowed Nolan to introduce greater thematic complexity.

Central to the conflict between Strauss and Oppenheimer is one of Nolan’s most significant – and most brilliant – whole-cloth inventions. Early in the film, Strauss misinterprets an interaction between Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein (Tom Conti), after which Einstein appears to give Strauss the cold shoulder. Strauss believes Oppenheimer intentionally turned Einstein against him, and this becomes one of the reasons for his petty grudge, but the true nature of the event is kept unclear. Later in the film (but earlier in the timeline), Oppenheimer reaches out to Einstein for advice when he’s concerned the atomic bomb will ignite the Earth’s atmosphere. All of these scenes with Einstein are made up, but they have elements of truth: Einstein and other scientists were afraid that the bomb could start a chain reaction that would destroy the Earth, and Strauss, Oppenheimer and Einstein were colleagues at Princeton after the war. Nevertheless, Nolan invents these scenes in order to give his film an ending that ties all of its strands together with incredible acuity. At the very end, when Strauss is denied as Secretary of Commerce, he complains again to an aide (Alden Ehrenreich) about how Oppenheimer turned Einstein against him. The aide retorts that perhaps Oppenheimer and Einstein were actually discussing something “more important” than Strauss. On that note, the Strauss storyline ends, and Nolan flashes back to that fateful conversation between Oppenheimer and Einstein. If you’ve seen the film, you will remember the final lines:

Oppenheimer: When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world.

Einstein: I remember it well. What of it?

Oppenheimer: I believe we did.

All that remains are the looks of horror on the scientists’ faces, some ominous images of America’s growing nuclear arsenal and terrifying hallucinations of the globe going up in flames. It’s hard to overstate the amount of complexity Nolan layers into these final moments. There are the literal and subtextual interpretations of the dialogue: the potential for actual world destruction resulting from nuclear war, and the destruction of the now defunct, pre-nuclear world order. There is the narrative irony that at this moment, and precisely because his mind is on the bigger picture, Oppenheimer doesn’t realize he is insulting the petty vanities of Strauss, and therefore setting off a chain reaction that will destroy his own world. There is the recollection of the Gita quote about becoming a “destroyer of worlds,” and by association a recollection of what else has been destroyed: Oppenheimer’s relationship with Tatlock, her life, and an alternative life in which Oppenheimer stuck more closely to his liberal principles. The implications even extend to Einstein: his early discoveries paved the way for the quantum physics that led to the atomic bomb. Einstein, too, was a “destroyer of worlds,” which explains his disturbed look that Strauss misinterprets as an insult. The single moment of Oppenheimer’s final line contains all this and more; it is one of the most thematically powerful moments in recent cinema. That the moment is entirely made up does not diminish its effect, because the scene doesn’t placate with the synthetic reliefs of fiction, it instead pushes the audience to face the reality of its story. With this incredible scene, and the incredible film before it, Nolan shows us how imagination can elucidate history.

Other “Revised and Visualized” Blogs:

Revised and Visualized: Joel Coen’s “Macbeth”

Revised and Visualized: Adrian Lyne Adapts Highsmith’s “Deep Water”

Oppenheimer’s fateful encounter with Einstein (Tom Conti)

*A quick note about the music: when a critic complains, as some have done, that there is “too much” music in a film like Oppenheimer, I take it as a sign that they’re unwilling to engage with the film as it is. Given how Oppenheimer is edited, the film is unimaginable without the score as a driving force. Take out the score and you have to change the edit, and at that point you’re just objecting to making a movie a certain way. Personally, I find all cinematic approaches – slow or fast-paced, loud or quiet – full of equal potential.