Buster Keaton, “The General” and White Supremacy

NOTE: An addendum has been added at the end of this blog which addresses the two Keaton biographies released in 2022 and adds some nuance to the questions discussed below.

In almost twenty years of reading film criticism, I’ve found that discussion of Buster Keaton’s 1927 Civil War comedy The General does not come with the same degree of ambivalence and caution that often attends evaluations of other Confederate-sympathizing American classics like The Birth of a Nation or Gone with the Wind. This is probably because, unlike the latter films, The General treats its subject matter with an unserious tone and, at first glance, does not appear to dig in to the racial politics of either its time or the time which it depicts.

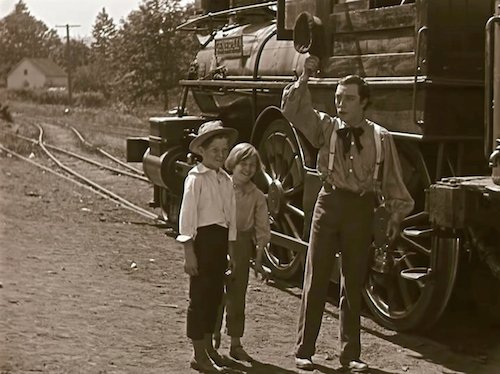

An image from the first five minutes of The General.

The General follows Confederate railroad engineer Johnnie Gray (Keaton) as he defends his town of Marietta, Georgia from some nefarious Union soldiers. Like most of the films which Keaton directed and starred in, the plot is minimal and often remembered only as an incidental setup for Keaton’s incredible array of sight gags and stunts. It’s not surprising, then, that the words “slavery,” “slave,” “Confederacy” or “Confederate” don’t appear at all in Roger Ebert’s 1997 Great Movies review of the film. A 2008 review at Slate praises the film for its attention to historical detail without reference to the Confederacy or slavery. The New York Times’ A.O. Scott doesn’t say much about the Civil War in his brief 2010 video essay celebrating the film. In their 2018 episode on The General, Unspooled hosts Paul Scheer and Amy Nicholson only passingly reference the Civil War subject matter. Reviews at BBC and The Guardian don’t touch on the Confederates or slavery. Whereas writers tend to feel obligated to acknowledge the horrors which films like Gone with the Wind and The Birth of a Nation defend, dilute or erase; that same obligation does not appear to extend to The General.

It’s well-known that a lot of revisionist Southerners engage in denialism about slavery in order to guiltlessly celebrate the cultural heritage of the Confederacy, as if the two weren’t connected. When dealing with films like The General which don’t appear to touch on slavery, it can be hard to tell if the filmmakers are coming at their history from a revisionist or full-on white supremacist perspective. Both are bad, but right-thinking people who might feel they have some leeway to forgive the ignorance, naiveté or bias of the revisionists often feel much less comfortable enthusiastically endorsing works of explicit white supremacy. If there’s a disparity between the ways The General and The Birth of a Nation are discussed, I think it’s because most people assume The General falls into the revisionist category.

Which prompts an interesting question: does the film itself support this reading?

No, it does not. The film is clear as day in its endorsement of the Confederacy’s ideology of white supremacy. And to be clear, I’m not referring to unconscious or subtle racism, but actual, undiluted white supremacy, a belief which poses blacks as an inferior race whose role in society is to serve whites.

A brief summary of the film is necessary: Keaton’s Johnnie Gray is a comically shy, but highly competent railroad engineer in Confederate Georgia. Winning his true love, Annabelle (Marion Mack), is conditional on his fighting in the Confederate army, because Annabelle’s Father and Brother are stern partisans. To his dismay, Johnnie is rejected from the army because he is deemed too valuable to the South as an engineer. After the war begins, some evil Union soldiers hatch a plot to invade Georgia by rail, a plot which only Johnnie has the skills to foil. After a long railroad chase which takes up the majority of the film, Johnnie joins the Confederates in a successful battle against the Union, winning himself honorary status as a soldier, and proving himself to Annabelle and her family. Throughout the story, a simple good-guys-versus-bad-guys schema is applied to the Civil War, with the Confederates being the good guys, and Johnnie’s hometown of Marietta depicted as a sort of bland, folksy utopia.

The first ten minutes of The General tell us everything we need to know about its embrace of the Confederacy and its white supremacy. The film begins with some establishing shots of Johnnie’s train (the titular “General”) and a title card establishing Marietta, Georgia. The train pulls into Marietta and Johnnie, the top engineer, alights in a static shot that sets up his character with the visual economy for which Keaton the filmmaker is so often praised. After giving a quick order to an underling (who receives it with an admiring nod), Johnnie is approached by two awestruck young boys who want to shake his hand. Johnnie complies with easygoing friendliness and lets the boys peek over his shoulder as he inspects the train.

The shot lasts only 15 seconds, but already we understand that Johnnie is competent, comfortable being in charge, respected in his community, and has a humble attitude toward that respect.

What follows is a reverse shot of a procession of passengers leaving the train. The shot lasts five seconds and begins with two black men, slaves, crossing camera carrying a massive trunk, followed by two Southern belles who wave at Johnnie, and then an assortment of ladies and gentlemen who also wave at Johnnie as they pass.

Visual logic would indicate that the two women immediately following the slaves are the slaves’ “owners,” but if that’s projecting too much, we can assume the slaves “belong” to someone in the group of passengers waving at Johnnie (I’m gonna drop the quotes now, but let it be known that if I use terms like these it’s not with any assumption of their legitimacy).

A lot is communicated with these two shots, lasting only 20 seconds, from the first two minutes of the film. Objectively, we pick up at least that 1) Johnnie is highly regarded by his fellow citizens, 2) he is by all appearances a good guy, 3) slavery exists in The General’s conception of the old South and 4) the fellow citizens who respect Johnnie are slave owners.

The visuals, and the narrative logic, indicate more. Remember that these shots are setting up Johnnie’s character, who is the hero and protagonist of the film. We are meant to know, right away, that Johnnie is a superlative person because everyone around him – at least, all the white people – treat him as such. The virtue which these Georgian slave-owners bestow on Johnnie must logically run the other way in order for the scene to make sense; either the slave-owners are themselves virtuous, or the respects they pay to Johnnie are meaningless, which it’s obvious they are not meant to be. I’m belabouring this point to offset any argument that the slaves and slave-owners are included in the shot strictly for the neutral purposes of “authenticity” or “visual detail” without any comment, from the filmmakers, on the legitimacy of slavery. This 20 seconds of footage establishes a positive status quo which the Union soldiers will later threaten, and, according to the film’s visual language, that status quo means black people in their “proper” place as slaves.

And what is The General’s particular conception of slavery? Is it the kind we’re used to from classics like Gone with the Wind, which depict happy black slaves who are simply thrilled to perform mandatory subservience for their benevolent masters? Decidedly not. Here, the black men’s labour is depicted as excessively back-breaking. The trunk they carry is huge, and the actors appear to actually struggle carrying it. The actor on the front side of the trunk keeps his head down except to check where he’s going, possibly because he’s been directed to do so. It’s a horrifying comparison, but Keaton and his filmmakers present these black men with the level of respect you’d expect for a pack animal (it’s worth pointing out, given the 19th century context, that the slaves are the only men onscreen not wearing hats). More disturbing still is that the film’s visual language would have us believe that this stomach-turning depiction of slavery is an image of how things ought to be.

You might say I’m reading too much into literally five seconds of film, but let’s consider a few things. Keaton, as a director, has been rightly praised for decades for his impeccable grasp of visual storytelling. At the outset of the film, the task for Keaton and his co-director Clyde Bruckmann was to tell us about the hero’s hometown, an uncomplicated haven which the hero will spend the rest of the movie defending. Well, the very first thing we see in the very first shot of the Marietta townspeople is a brutal image of slavery. It is the only depiction of slaves or slavery in the film. There are no other black faces onscreen, as far as I can see, and this conception of slavery is not challenged or subverted, or even contrasted with something more humane. Considering Keaton’s aptitude for visual storytelling, and considering that this is how he chose to set up his sentimental story about the Old South, is it a stretch to infer that, from the perspective of the film, the Old South meant the total physical domination of Black people? We’ll never know Keaton’s mind, but it’s useful to ask: Why are the slaves front and centre in the shot? Why is the trunk so excessively large and why is it important we see the actors struggle to carry it? Why is this the image Keaton and his team chose to set up Marietta, and by extension Georgia, the Old South, and the Confederacy? None of the probable answers are very comforting.

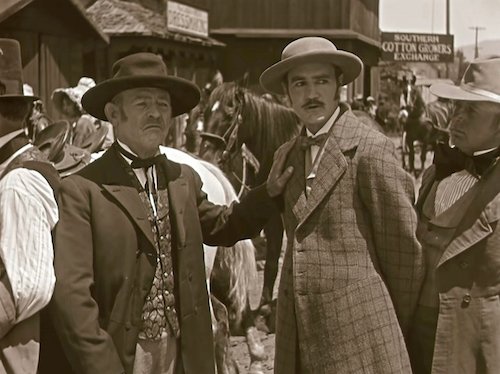

If there’s any doubts about The General’s white supremacy after the first two minutes, these should be dispelled by minute ten. Soon after Johnnie’s arrival in town, the beginning of the Civil War is announced and Johnnie races to join the Confederate army alongside Annabelle’s Father and Brother. It’s here, five minutes in, that we get a few wide shots of Marietta, and the production design is telling. Marietta is presented as a generic-looking old western town; its buildings and storefronts free of signage with four visible exceptions: a Confederate flag, and signs reading “Recruiting Office,” “Stove Wood and Lamp Oil” and, crucially, “Southern Cotton Growers Exchange.”

The image above shows Johnnie enthusiastically placing himself at the front of the line to enter the recruiting office, and since the shot is composed to place the signage in almost dead-centre, what exactly these Confederates – and our hero – are signing up to fight for could not be more salient:

After Johnnie is rejected from the recruiting office, he runs into Annabelle’s Father and Brother, who scowl in judgment upon learning Johnnie wasn’t accepted by the army.

Notice that the sign which is framed to be legible at all times is the one reading “Southern Cotton Growers Exchange.” Someone eager to defend the movie might argue that the sign was put there simply to colour the scene with “historical detail,” but consider the overall scarcity of production design. For the entire duration of the film, there is only one sign visible in Marietta (“Stove Wood and Lamp Oil”) which is not explicitly concerned with the Confederate army or slavery. In establishing Marietta, Georgia, the old South and the Confederacy (all great things, according to the film), Keaton and his team can hardly tell us anything besides that these were slave-owners. This is not an exaggeration; watch the first ten minutes and ask, what do we learn about Marietta that isn’t connected to slavery? That people live there? A train passes through? They like stove wood and lamp oil?

With all this in mind, it’s hard to think of Keaton and his team as revisionists who chose to celebrate the Confederacy for its cultural value, or whatever. This would of course be an execrable goal in and of itself; only less execrable, perhaps, than an outright tribute to white supremacy and slavery.

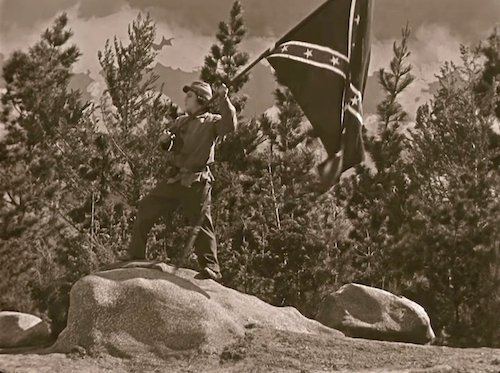

I suppose it’s easy to overlook or forget these details when the action moves on to the spectacular railroad chase that takes up most of the film. After the first ten minutes, slavery is not explicitly referenced, but the climactic battle does reinforce the film’s sentimental perspective of the Confederate army. Johnnie’s transformation from misunderstood underdog to heroic soldier is signaled by his donning the Confederate uniform, and cemented when, at the film’s peak, he relieves a wounded soldier of a giant Confederate flag and flies it proudly.

This is the final moment of the climax. The Confederates have won, the narrative conflict has been resolved and order restored. Johnnie has overcome all of his obstacles and achieved his goal of becoming a war hero to impress Annabelle. The triumphant flag waving is emblematic of all of this, and it’s clear, from all the evidence above, that the man who composed this shot and performed this scene knew full well that this flag meant slavery. What is not clear is if the flag meant much else, to Keaton and his team, besides slavery.

Here, some fans of The General might accuse me of being dishonest, because the above moment doesn’t simply end with Johnnie waving the Confederate flag. After his moment of glory, it’s revealed Johnnie is actually standing on a Confederate general, and he comically stumbles when the general stands up.

After Johnnie is toppled over and the general chastises him, the shot fades to black and the film moves on to the denouement. Since the triumphal moment is interrupted by a joke at Johnnie’s expense, some very charitable viewers might be tempted to argue Keaton was engaging in some form of ironic or satiric subversion, or that the film’s comedy somehow undermines its plot’s obvious inclination toward the Confederates.

I think this is really stretching it. Everything about the film’s visual language would indicate that the audience should be cheering when the Confederates win and nothing about the film’s visual language invites us to question or probe too deeply into what’s happening on its surface. The simple presence of levity doesn’t mean the core subject of a film is being mocked or undermined (the Lethal Weapon movies aren’t critiques of macho action pictures simply because they have jokes). While jokes at the protagonist’s expense, in some movies, function to move the audience to question that protagonist, in The General, Johnnie’s pratfalls simply humanize him and encourage the audience to root harder for him.

It is also important to note that while Johnnie’s manhood is underestimated when he is rejected from the army, the film does not pose a critique of these gender expectations, as you might expect from a modern movie about a romantic underdog. Annabelle’s Father and Brother’s disapproval of Johnnie after he’s rejected from the army makes them stern, but not villainous; they are presented as heroic throughout. The Father and Brother characters function as the gatekeepers of an acceptable definition of manhood, and Johnnie’s challenge is not to refute their definition, but to prove to them that he belongs within its bounds. Since the Father and Brother are also the film’s model Confederates, it’s hard to argue The General is treating them or the Confederacy with irony. The romantic narrative has a very simple symmetry: at the beginning, Annabelle tells Johnnie “I don’t want you to speak to me again until you are in uniform;” the very last shot of the film has Johnnie, in Confederate uniform, embracing Annabelle. One can imagine a movie that upends Southern gender dynamics to pose a sly critique of the Confederacy; this is not that movie.

Taking all of this into account, it appears unambiguous to me that The General is a work of overt white supremacy. What is less obvious is if Buster Keaton was himself a white supremacist, or simply utilized white supremacy because he thought it would make his movie more successful (the possibilities are not good). About The General, Keaton is supposed to have said “I was more proud of that picture than any I ever made. Because I took an actual happening out of the […] history books, and I told the story in detail too.” The General is based on a memoir called “The Great Locomotive Chase,” which recounts an actual episode of the Civil War. The memoir is told from the Union perspective, but Keaton flipped this, supposedly because he didn’t believe audiences would accept the Confederates as villains. Multiple articles online reference this supposed quote of Keaton’s which explains his reasoning: “It’s awful hard to make heroes out of the Yankees.” If these quotes are accurately preserved, they suggest, on Keaton’s part, a personal investment in the history of the Civil War. Considering how that history is portrayed in the film he made, white supremacy could have figured into that investment. Who knows. Certainly, the perspective flip and the film’s white supremacist content indicate Keaton and his team were happy to appeal to Southern devotees of the Confederacy. Recall that in 1926, the American Civil War was not an historical abstraction; many former Confederates and slave-owners, and even more of their children, were very much alive. When Keaton fretted over “audiences,” he must have had these people in mind. Consider also that in the mid-1920s the Ku Klux Klan were at the height of their powers. In 1924, two years before Keaton made The General, Klan membership had reached its peak of 1.5-4 million Americans (about 1-3% of the US population). In 1926, a Klan chapter head became governor of Alabama. At the very least, you might say Keaton saw which way the wind was blowing, and this could explain the film’s explicit nods to white supremacy.

Recently, HBO Max added an intro to Gone with the Wind, putting the film in its proper context. The intro rightfully acknowledges the film’s racism and its whitewashed depiction of slavery. I might be wrong, but I think the average cinephile would think of The General as being less racist than Gone with the Wind (all the aforementioned reviews would appear to support my assumption here). For all of Gone with the Wind’s horrors, it at least (emphasis on “least”) provided space for Hattie McDaniel to do some trailblazing (McDaniel became the first black person to win an Oscar for her indelible performance). In The General, the only black people we see are all but faceless, completely denied any dignity, presented as nothing but physical bodies belonging to white people; this perspective was intentionally delivered by Keaton as nostalgia for the Klan members and former Confederates in the film’s audience. With all this in mind, it’s a little shocking that only two years ago Peter Bogdonavich released a documentary entitled “The Great Buster: A Celebration,” in which a parade of critics and celebrities pay tribute to Keaton and The General without probing into any of this.

Perhaps The General and Keaton are due for a little context.

ADDENDUM (04/19/22):

Since I posted this in 2020, two Buster Keaton biographies have been released: Buster Keaton A Filmmaker’s Life by James Curtis and Camera Man by Dana Stevens. Also, I discovered something I’d missed: Buster Keaton’s own autobiography My Wonderful World of Slapstick, published in 1960. After looking at these I believe I can add a little more nuance to some of the issues discussed above, though parts of Stevens’ book reinforce my observation that cineastes are quick to give Keaton a pass.

First, on the question of Keaton’s personal beliefs, there’s some evidence that he wasn’t ideologically white supremacist or pro-slavery. In his autobiography, he speaks admiringly of his father’s relative lack of racial prejudice and his generosity toward a particular black performer. It’s a short passage but it seems to come from the heart. Of course, Keaton would have written these words over thirty years after shooting The General and could have changed his mind in that time. The impression I get from the biographies, though, is that Keaton’s choice to favour the Confederates in The General was primarily out of sensitivity toward the side that lost the Civil War, at a time when the conflict was still in living memory.

James Curtis’ book – which goes into much detail regarding the production of The General but does not reference Keaton’s nods to slavery – includes a Keaton quote that concisely explains Keaton’s choice to tell the story from the Confederates’ side:

“They lost the war anyhow, so the audience resents it. We knew better. Don’t tell the story from the Northerners’ side – tell it from the Southerners’ side.” (pg 288)

You can read into that quote a kind of liberal sympathy for the underdog, although it’s obvious that sympathy was applied to the white Southerners who lost the war and not the black Southerners who were enslaved. I don’t think the quote depicts a purely (if perversely) humanitarian Keaton, either. His concern about “the audience” was a business concern: raising the ire of too many former Confederates would have hurt his picture’s bottom line. Keaton’s willingness to pander to the Southerners extended as far as casting black actors as slaves and depicting them doing rather gruelling labour. If he wasn’t personally white supremacist and pro-slavery, he was clearly happy appealing to those sentiments to help his business (his strategy wasn’t successful; The General was a huge flop).

Interesting, then, that in Camera Man Dana Stevens refers to The General as an “essentially apolitical story” (pg 192):

Keaton’s character, Johnnie Gray, is a southern railroad engineer who tries and fails to enlist in the Confederate army not out of patriotic duty but in order to impress the girl he loves[…]

When Johnnie sets off in pursuit of the Union spies who have hijacked his beloved train, it’s not in defense of the Confederacy’s property but his own. The only thing he cares more about than Annabelle […] is that train, the “General” of the title. In one of the most memorable sequences Johnnie scrambles across the top of the train as it hurtles past fields full of soldiers on horseback riding into battle. He’s so focused on keeping the wood-burning engine stocked with fuel that he’s oblivious to the historic events unfolding around him.

I should note that here Stevens is partly characterizing the critic Robert Sherwood’s case against The General (that it is distastefully apolitical), though if I’m reading her correctly, she’s also giving her own summation of The General’s politics. If I’m correct (and if I’m not, all apologies to Stevens), I think this is a great example of a Keaton fan’s reluctance to face up to the white supremacy of his greatest and most celebrated accomplishment. For one thing, Keaton’s choice to lionize the Confederates to avoid offending them and their descendants was political in and of itself. Also, Stevens’ second paragraph above implies a comedic dynamic which I don’t think is present in the film. I can imagine a comedy where a self-interested character gets involved in a war only to fulfill his own goals (say, Kelly’s Heroes), but nothing in The General suggests that Johnnie’s goals aren’t aligned with the Confederates’. If the dynamic Stevens describes was accurate to the film, you could imagine there may be scenes where Johnnie acts against the Confederates to serve his own ends, even in a minor way, but no such scene exists. When Johnnie flies the Confederate flag at the end, there’s no reason to think he’s not doing so sincerely. Even the example Stevens gives is both unconvincing and factually incorrect. In the shot she describes, Johnnie is refuelling a different train than his General, which is in the hands of the Union soldiers at this point of the story. Stevens loads this moment with unwarranted meaning, but she forgets an earlier scene when Johnnie is more than willing to blow up his beloved train to stop the Union and assist the Confederates. He is not comically disinterested in the historical scenario: he is an active, and decisive, participant.

Stevens is not indifferent to the racially problematic elements of Keaton’s films. She devotes a chapter decrying and analyzing Keaton’s use of race humour in many of his shorts. This chapter (“The Darkie Shuffle”) portrays Keaton as a man who had much admiration for some black performers, but who had no issue with getting laughs using blackface or other race humour that would be offensive by today’s standards. Stevens even goes so far as to describe Keaton as a product of Jim Crow (although there’s a sense in which being a “product of” something does relieve one of accountability). After dealing frankly with the racism behind some of Keaton’s humour, Stevens ends the chapter with this description of a blackface scene from his film College:

[…]Keaton sometimes appears to deploy the familiar stereotypes of blackface minstrelsy […] while also exploring how these tropes change meaning depending on who uses them, and why. By transforming into a stereotypically shuffling waiter when and only when his character’s racial identity is called into question by a white customer, it is as if Keaton is acknowledging the performative nature of race in the segregated social world his characters, his audience, and he himself inhabit. His body understands, in a way it seems his conscious mind never did, that the “darkie shuffle” is by definition a put-on, and that donning blackface as a white man is an act of symbolic violence. (pg 228)

This registers to me as a rather transparent attempt to teach modern viewers how to tolerate scenes which in other contexts they would find deplorable, in order to preserve an understanding of Keaton as a relatively innocent product of his time. Steven’s equivocal language (“sometimes appears to,” “it is as if,” “His body understands”) carries the implicit acknowledgement that she’s not referring to anything that likely factored into the production of these scenes in reality, but rather an abstract way to revise these scenes now. This isn’t a terrible aim: it’s better to appreciate these scenes the way she describes than the way Keaton intended. That said, looking at Keaton this way necessitates a certain willed blindness to his actual motivations, a blindness that’s easier to maintain if you ignore that in The General Keaton knowingly shot images of black suffering to pander to racist Southerners. When Keaton framed the shot of the black slaves almost collapsing under the weight of that massive trunk, it’s doubtful that either his mind or his body failed to understand the violence of what he was depicting.

So once again I am flummoxed that Keaton escapes any criticism for pandering to Southern racists by making a pro-Confederate movie at a time when the KKK was dominant in American society. After all, a critic like Stevens is not exactly slow to dial up the outrage metre: take this podcast where she accused Sofia Coppola of engaging in “plantation nostalgia” for her film The Beguiled. If The Beguiled is plantation nostalgia (I don’t think so), The General is plantation propaganda, made at a time when such propaganda carried a lot of weight in American culture. My mind turns to an analogy that some might find extreme, although I don’t see how it is: imagine that in the 90s there was a resurgence of Nazism in Germany, to the extent that German Jews were routinely lynched and legally segregated from other Germans. Imagine if in that context, a really funny German comedian made a technically impressive WWII comedy that made heroes out of the Nazis and showed Jews in concentration camps in a positive light. Even if this movie was 100 times more impressive than The General, would today’s critics celebrate it without even mentioning the political context? So, again: why does Keaton get a pass?