The Best Films of 2023, According to Me

2023 was a pretty good year for movies, both in the visionary and conventional modes. I’m as excited as everyone else that because of Oppenheimer and Barbie Hollywood appears to be moving in the direction of originality, although, when I look at lists for the most anticipated movies of 2024 - for example - I don’t exactly see a horizon full of imagination and invention, so let’s wait and see. That said, if we don’t get an Oppenheimer every year, but we get a few mainstream comedies as good as No Hard Feelings and You Hurt My Feelings, I’ll call this a renaissance anyway.

19. The Boy and the Heron (directed by Hayao Miyazaki)

More a cerebral pleasure for me than an emotional one, but the incredible animation and Joe Hisaishi’s absolutely gorgeous score must be experienced.

18. No Hard Feelings (directed by Gene Stupnitsky)

Becomes cheap and conventional in its last thirty minutes, but until then this is full of big laughs, probably ninety percent of the credit for which should go to Jennifer Lawrence, who makes things funny which might be hack on the page. Okay, maybe eighty percent credit to Lawrence, and the other twenty percent give to Andrew Barth Feldman, very good as the sheltered zoomer whose parents hire Lawrence to deflower.

17. Master Gardener (directed by Paul Schrader)

Can a movie be both risible and good? This feels like the third part in a trilogy of sorts by Paul Schrader, after First Reformed and The Card Counter, though all three address themes and narratives which Schrader has been dealing with his entire career. While First Reformed was a movie in which every element felt perfectly realized, and The Card Counter had a lead character/performance that was compelling while the elements surrounding that performance were only passable, Master Gardener is a movie in which all the elements surrounding the compelling lead character/performance are laughable. But that lead performance – by Joel Edgerton as an ex-Nazi and current eponymous gardener – is highly compelling, and unimpeachable. The austerity and focus of Edgerton’s acting is scary in the best way.

16. Past Lives (directed by Celine Song)

Fairly deserving of all the praise; can’t think of many recent romances that generate the emotional power of this film. Credit to director Celine Song for maintaining a delicate tone throughout, but I’d like to single out two other items I thought were very important to this film’s power. First, the cinematography by Shabier Kirchner, which lends a subtle scale – almost grandeur – to this intimate story. Second, the totally endearing, vulnerable, and very moving work of actor Teo Yoo as the romantic lead. The pained but durable resignation he displays at the end is an example of the kind of cinematic heroism that is actually useful, as it provides a powerful standard for the rest of us merely-human, broken-hearted slobs to live up to amidst our daily disappointments.

15. Barbie (directed by Greta Gerwig)

As Barbie movies go, I think we can all agree this could be much, much, MUCH worse. The creativity and intelligence with which Gerwig and Baumbach handled this IP is world-class, and a valuable lesson which I’m sure will be honoured completely by Lena Dunham’s Polly Pocket movie. What I like most about Barbie is just how weird and goofy it is. When Gosling and the other Kens march on their invisible horses, although it’s a steal from Monty Python, it’s heartening that in 2023 something Python-esque made it into a major movie. It feels like the American movie comedy has begun a reanimation process, and to see glimmers of Python and ZAZ in one of the biggest movies of the year is exciting indeed.

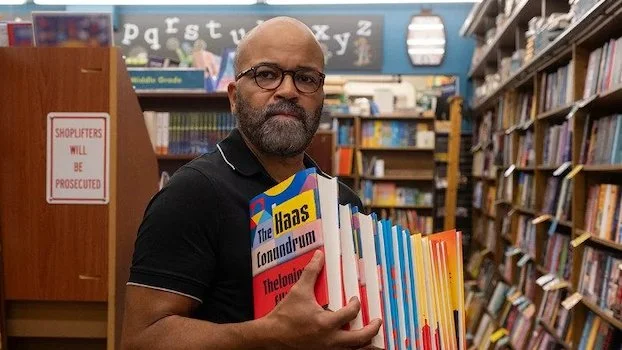

14. American Fiction (directed by Cord Jefferson)

Speaking of the rejuvenation of American comedies, here’s an example in the highly-erudite, nuanced, Woody Allen/Albert Brooksish model. Jeffrey Wright stars as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, a writer of niche fiction who suffers from the expectation that, because he’s black, his books should “say something about the African American experience.” In a spiteful gesture, Monk writes a parody of a Push-style novel, which the white publishing world takes very seriously and heralds as the next big thing in American literature. What’s lovely about the movie – and Erasure, the novel on which it’s based – is the proportion of attention allotted to Monk’s dysfunctional but not at all stereotypical family. In novel and film, the takeaway is clear but not pressed-upon: “the African American experience” is as varied as the media representation of that experience is narrow and limiting. The movie is full of great jokes, at several points the theater I saw it in (packed with bougie Toronto whites probably not a million miles away from the movie’s targets) was full of uproarious laughter. Jeffrey Wright appreciators will be happy to see him nail a starring role.

13. May December (directed by Todd Haynes)

Very provocative and not at all as black and white as some critics would like to think. I was taken by the three central performances, the subtly encroaching humour, and the film’s willingness to leave the bizarre relationship at its centre an unknowable void. Charles Melton cannot be praised enough, his character is an unsolvable mystery, and he gives a performance full of humanity without tipping the audience off to any easy interpretations.

12. The Five Devils (directed by Léa Mysius)

Movie about a little girl who can see into the past using her supernatural sense of smell, but this isn’t a comedy or a corny children’s film. Vicky’s (Sally Dramé) ability allows her to witness the pasts of her parents (Adèle Exarchopoulos and Moustapha Mbengue) and piece together a family mystery that puts her own existence in a surprising, painful context. It’s a weird premise, to be sure, but somehow it all plays very naturally, and I found I was quite involved by the story’s end. The cinematography by co-writer Paul Guilhaume is mesmerizing, the three actors mentioned above are all fantastic, and Swala Emati is bewitching as Mbengue’s mysterious sister. The movie peaks when Exarchopoulos and Emati perform a somewhat reluctant, very funny and kind of moving, karaoake version of Total Eclipse of the Heart. Also, if you watch this movie and can figure out why it’s called “The Five Devils,” please let me know.

11. Return to Seoul (directed by Davy Chou)

The best movie of 2023 about a western Korean millennial evaluating her connection to her homeland. In this case, said millennial was adopted by French parents at a young age and at first strikes an indifferent pose toward her Korean heritage, only winding up in the titular city by mistake after a Japanese vacation doesn’t pan out. Of course, her actual feelings about Korea are much more complicated than she pretends, and her tentative steps towards reuniting with her birth parents occasion a lot of pain and confusion. Ji-min Park, as the elusive protagonist, is lively, dimensional and never predictable; it’s a star-making role, or it would be if I decided that sort of thing.

10. You Hurt My Feelings (directed by Nicole Holofcener)

Another highly successful, old fashioned American comedy; probably the English-language film that made me laugh the most this year. Julia Louis-Dreyfus, flawless as ever, plays a novelist who overhears her husband knocking her latest book; the accidental revelation causes a lot of (relatively light and comical) marital strife. It’s not heavy, but it is relatable. I admired the way the characters wrestled with mid-life mediocrity, a condition that’s too common to jerk any tears, and which therefore feels novel for a film. Holofcener’s script has a typically high proportion of laugh out loud lines, Louis-Dreyfus predictably nails all of them, and Michaela Watkins is hilarious as Louis-Dreyfus’ sister.

9. Fallen Leaves (directed by Aki Kaurismäki)

If you are familiar with the films of Aki Kaurismäki, this will not blow your mind. At times, it feels like a remake of his 1986 film Shadows in Paradise, also a romance between working class Fins. Alma Pöysti is a little more active than his usual heroines, but otherwise Kaurismäki’s vision of grubby urban locations and laconic loners hasn’t changed much in forty years. These, of course, are all positives; I love Kaurismäki’s cinematic vision, where human warmth glints weakly but durably through urban morass. Some directors, because of the consistency and distinctiveness of their aesthetic, create an identifiable world through their films, “cinematic universes” far more cohesive and imaginative than the films to which that label has lately been applied. Kaurismäki is one of the most endearing of these directors, as is the next one…

8. The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, The Swan, The Rat Catcher and Poison (directed by Wes Anderson)

“I’ve never seen anything like it” is not a phrase I would expect to apply to the new Wes Anderson output, given how similar his films are to each other. While his enjoyable Asteroid City did not offer many aesthetic surprises, these four short films are full of them, demonstrating an unprecedented approach to literary adaptation. Each film is based on a Roald Dahl short and the writer’s prose is spoken continuously and direct to camera by the actors, the role of narrator shifting from character to character. The actors perform the narrative, but on straightforwardly artificial sets which are often reconfigured mid-shot by on-screen crewmembers. Somehow, suspension of disbelief is enhanced, not broken, by these choices, and the films don’t come off as theater pieces, although clearly theater was a major inspiration for Anderson. Dahl’s words are conveyed with bottomless nuance and sly humour by Benedict Cumberbatch, Dev Patel, Ben Kingsley, Richard Ayoade, Rupert Friend and Ralph Fiennes as Dahl himself (I guess Dahl didn’t write a lot about women, because I don’t believe any speak a word in these films). Through Dahl, Anderson hits new registers than he has before; The Swan could be the most emotionally raw work he has ever done. These films cast a weird spell.

7. Priscilla (directed by Sofia Coppola)

One day, Sofia Coppola will get the acknowledgement she deserves, meaning she’ll be acknowledged as one of the best directors of her era. Few directors conjure so much depth so invisibly. In that sense, stars Cailee Spaeny and Jacob Elordi are the perfect match for Coppola, as Priscilla and Elvis Presley they’re worlds unto themselves. Spaeny is a virtuoso, her Priscilla receives everything tradition declares a girl should want but decides, not without heartbreak, that it’s not enough; Spaeny and Coppola articulate this progression with miraculous subtlety. Elordi does something that must be a lot harder than it looks: he plays one of history’s most overexposed public figures totally out of the context of his fame and legend. His Elvis is a strange, lonely man whose extravagant costumes are like a shell to keep the world out. As with all of her films, Coppola creates a distinctive mood peculiar to the time and place of her story, all the more impressive here given that Priscilla was shot in Toronto.

6. Rotting in the Sun (directed by Sebastián Silva)

Sebastián Silva proves once again he’s the modern-day Fassbinder, this time with a misanthropic comedy that’s a combination showbiz satire and ruthless essay on class and social media. Silva plays a fictionalized version of himself – at least, one hopes it’s fictionalized, given the addiction and suicidality he performs here – who tries and fails to treat his depression with a trip to the Mexican nude beach Zipolite, which according to the film is the site of an endless gay orgy. What Silva finds instead of relief is Jordan Firstman, an influencer who plays himself as the most relentlessly superficial, self-centered, self-aggrandizing and hilariously ignorant man on Earth – it’s a legendary comic performance. Silva and Firstman agree to collaborate on a television show, and it would spoil the film to say how this effects Silva’s maid (Catalina Saavedra, stellar); but suffice it to say, the film’s observations about class and social media are dispiriting, incisive and amusing.

5. Fremont (directed by Babak Jalali)

When Jim Jarmusch retires, I’m heartened that Babak Jalali will still be making films. Here the Iranian director has made a black and white slice of life that has the patience, pictorial elegance and quietly spontaneous performances of that director’s best work, which is the highest compliment imaginable. Fremont tells the story of Donya (Anaita Wali Zada), an Afghan working at a fortune cookie factory in the titular Californian city. A former translator for the U.S. military before her country was reclaimed by the Taliban, Donya exists in a limbo of guilt and dislocation, but she’s also open to the beauty of her new life, and how she deals with that ambivalence provides the tension of the film. Zada is wonderful, engaging and subtle, and surrounding her are a lot of memorable, charming characters, including a surprisingly moving Gregg Turkington as Donya’s initially reluctant psychiatrist. The setting of the fortune cookie factory might indicate a type of cheap mid-oughts whimsy that’s gone out of fashion, but nothing Jalali does here is cheap. The fortune cookies figure into the story a number of ways, none of them predictable, and Jalali’s brilliant use of them is a practical demonstration of one of his themes: that sometimes the smallest things provide the most meaning.

4. Full River Red (directed by Yimou Zhang)

Read this if you want to hear me argue why Zhang’s film may be an act of subversion, but even if I’m wrong and Full River Red is the Chinese propaganda it appears to be, this is a singularly dark cinematic vision from one of the greatest directors in history and worth seeing for that reason alone.

3. Killers of the Flower Moon (directed by Martin Scorsese)

Sometimes, from the second it’s released, there’s no doubt a movie will go down in history as one of the greatest ever. I think there’s a narrative about Scorsese and his fellow movie brat directors that they made their best movies between thirty and fifty years ago and what they’ve done since, while it might be good, is not up to par with their greatest accomplishments. I think in general this is incorrect and it’s especially incorrect with Scorsese, whose natural mastery of the cinematic form has only grown more natural and more masterful over time. I think The Wolf of Wall Street and Silence are two of Scorsese’s very best films, and Killers tops them; it’s a movie that utterly transports you to the 1920s Oklahoma hills and to the blackest depths of human iniquity. Also, check this out if you want to read the only blog on the internet comparing Killers to a little-known Boris Karloff picture.

2. Oppenheimer (directed by Christopher Nolan)

Is Oppenheimer really “better” than Killers of the Flower Moon? Not really, but I’m giving it the edge for what I find to be its advancement of the cinematic form. The imagination, innovation intelligence and courage with which Nolan adapted this nonfiction biography is unprecedented. Nolan proved it’s possible to realize a complex historical narrative with the scale and style of one of his action movies, but without the action, and without compromising the accuracy or complexity of the story, and that doing so could produce a bigger hit, in 2023, than any of the year’s Marvel movies. Let that sink in, and while you’re doing that read this for my analysis of how Nolan turned a dry, exhaustive biography into an exciting blockbuster. To me, the most exciting cinematic question right now is: what will Christopher Nolan do next? (Hopefully not a Bond movie.)

1. River (directed by Junta Yamaguchi)

Speaking of advancing the cinematic form, here’s an endlessly charming comedy that’s also an experimental narrative, incomparable to any other movie except the last one by this writing/directing team, Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes. Both films revolve around an ingenious chronological device; in River, the workers at a wintry Japanese spa find themselves stuck in an endless two-minute time loop, at the end of which they continually wind up back where they started two minutes earlier. Over the course of an hour and a half, the same two-minute span of time is repeated, well, I guess about forty-five times, and while you’d think it would get old after a while, director Junta Yamaguchi and writer Makoto Ueda would scoff at such unimaginative thinking. The storytellers brilliantly set up a number of plot points and jokes which are complicated by the premise, as the characters figure out how to use the endless two minutes to try to understand what’s going on and deal with their own personal issues. At the centre of it all is a charming and hilarious performance by Riko Fujitani as a woman who may have some insight into what’s going on. Without giving too much away, at its heart River is a romantic comedy, and Fujitani shares the charisma and madcap humour of classic Hollywood screwball comediennes like Barbara Stanwyck and Katherine Hepburn. On top of being very funny, and dazzlingly inventive, River has moments of startling, ethereal beauty, as the characters learn some things about the fleeting temporality of life. After watching Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes, I wrote that “I left wanting to immediately watch [that film] again, and plenty more movies with these actors, please.” Well, I got my wish, as all the same actors appear here; it’s a really fun, memorable group, with Fujitani being the MVP.

I saw River at an Asian film festival hosted by TIFF, not sure if or when it will get a full American release. I imagine it will be a hard movie to find, and the forgettable English title doesn’t help. Hopefully, River gets some appreciation this side of the globe before some kind of Yamaguchi retrospective twenty years from now. If you get a chance to see it any time soon, DO NOT PASS. River is on the cutting edge.